Richard D. Wolff and Michael Hudson argue that America’s crisis is not geopolitical, but systemic.

In Washington, China is routinely described as an external threat — an aggressive rival undermining American prosperity through unfair trade, state subsidies, and authoritarian planning. But according to economists Richard D. Wolff and Michael Hudson, this framing gets the story exactly backwards. The problem is not China. The problem is the economic system the United States has chosen to defend.

In a wide-ranging discussion on global political economy, Wolff and Hudson argue that the decline of U.S. economic power is not the result of policy mistakes or foreign manipulation, but of capitalism’s evolution into a finance-dominated system that prioritizes rent extraction over production. China’s rise, by contrast, reflects an alternative approach — one that subordinates finance to industrial development and long-term planning.

“This isn’t about whether the U.S. can outcompete China,” Wolff argues. “It’s about whether an economy organized around financial profits can survive in a world that still requires production.”

The Myth of Free Markets and the Reality of Power

For decades, American elites promoted the idea that free markets naturally generate efficiency, innovation, and growth. State planning, by contrast, was supposed to be inefficient, rigid, and doomed to stagnation. China’s economic trajectory has exposed this narrative as ideological rather than empirical.

“What China did,” Hudson explains, “was keep control over the basic infrastructure of its economy — land, banking, and industry.”

Rather than allowing private finance to dominate capital allocation, China uses public banks and state institutions to channel credit into manufacturing, transportation, energy, and technology. This is not central planning in the Cold War sense, but it is planning nonetheless — and it has produced results.

Meanwhile, in the United States, capital increasingly flows not toward expanding productive capacity, but toward speculative activity. Corporations borrow money not to build factories or raise wages, but to buy back shares and inflate stock prices. Housing, healthcare, and education become vehicles for rent extraction rather than social provision.

“The U.S. economy,” Wolff notes, “rewards making money without producing anything.”

Financialization and Class Power

At the center of Wolff and Hudson’s critique is financialization — the process by which finance comes to dominate economic and political life. This is not a neutral evolution. It reflects a shift in class power.

“When finance takes over,” Hudson argues, “the economy stops serving workers and starts serving creditors.”

The consequences are visible everywhere: rising household debt, stagnant wages, decaying infrastructure, and extreme inequality. The working class is forced to borrow simply to access basic necessities, while financial institutions extract interest, fees, and rents.

This is not accidental. It is the logical outcome of a system in which policy is shaped by those who benefit from asset inflation rather than from broad-based growth.

“Financial capitalism,” Wolff says, “is capitalism eating itself.”

Trade Wars as Political Theater

Rather than confronting these structural problems, U.S. policymakers have turned to tariffs, sanctions, and trade wars — particularly against China. Wolff and Hudson see these measures as largely symbolic.

“You cannot tariff your way back to industrial leadership,” Wolff argues.

Trade wars may appeal to domestic political audiences, but they do little to rebuild productive capacity. In fact, they often raise prices for consumers while leaving corporate behavior unchanged.

Hudson adds that sanctions and tariffs have pushed China to accelerate domestic innovation and strengthen ties with non-Western trading partners.

“The more the U.S. tries to isolate China,” he says, “the more it isolates itself.”

From this perspective, trade policy functions as a distraction — shifting blame outward rather than confronting the failures of U.S. capitalism.

Two Economic Models, One Global System

Wolff and Hudson emphasize that the current conflict is not best understood as a clash between nations, but as a struggle between economic models.

“This is not capitalism versus socialism,” Wolff explains. “It’s finance capitalism versus production-oriented economies.”

China’s system is hardly egalitarian. But it does limit the power of rentiers and preserves the state’s ability to guide development. Land remains publicly owned, infrastructure investment is prioritized, and banks are prevented from dominating the economy.

Hudson contrasts this with the U.S., where rent extraction defines key sectors of everyday life.

“Housing is no longer shelter,” he says. “It’s a financial asset. Education isn’t a public good — it’s a debt trap.”

The result is an economy that enriches asset holders while imposing rising costs on workers.

Empire Without Industry

Historically, Hudson notes, financial dominance often emerges at the end of imperial cycles. When industrial leadership declines, empires increasingly rely on debt, speculation, and military power to maintain influence.

“Finance becomes a substitute for production,” he argues. “And that never ends well.”

Wolff draws similar parallels, warning that military spending and sanctions cannot compensate for economic decay.

“No empire has survived by denying its own decline,” he says.

Yet this denial is precisely what defines much of contemporary U.S. policy. Rather than rebuilding infrastructure or democratizing economic power, political leaders double down on militarization and financial dominance.

Why China Is Really Feared

According to Wolff and Hudson, China’s real threat is not military or ideological, but demonstrative.

“China proves that another way is possible,” Wolff says.

For elites invested in neoliberal orthodoxy, this is deeply unsettling. If markets require planning, if finance must be restrained, if public ownership can coexist with growth — then decades of economic dogma collapse.

Hudson puts it bluntly:

“The fear is that other countries will follow China’s example.”

From Latin America to Africa, governments are searching for development models that do not subordinate national economies to global finance. China’s experience, whatever its contradictions, offers one such model.

The Limits of Reform

Could the United States change course? Wolff and Hudson are skeptical — not because it lacks resources, but because it lacks political will.

“To challenge financial power,” Wolff says, “you have to confront the class that controls policy.”

Such confrontation would require breaking with decades of bipartisan consensus, democratizing credit, and redefining economic success in terms of social need rather than asset prices.

Hudson frames the choice starkly:

“Either the economy serves society, or society serves creditors.”

So far, the U.S. has chosen the latter.

Conclusion: Capitalism’s Reckoning

Wolff and Hudson’s analysis points toward a conclusion that mainstream discourse avoids: the crisis facing the United States is not Chinese competition, but capitalism in its financialized form.

China’s rise has simply exposed the contradictions. An economy organized around rent extraction cannot indefinitely compete with one oriented toward production. Nor can it provide rising living standards for the majority.

As Wolff concludes, “This is not about China winning. It’s about whether the system we’re living under still works.”

For the Left, that question demands more than defensive nationalism or nostalgia for a lost industrial past. It demands a serious reckoning with power, class, and the economic structures that shape our future.

Who is Who

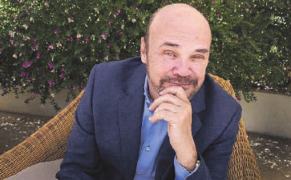

Richard David Wolf,

born April 1, 1942, is an American Marxist economist known for his work on economic methodology and class analysis. He is Professor Emeritus of Economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and a visiting professor in the Graduate Program in International Affairs at The New School. Wolff has also taught economics at Yale University, the City College of New York, the University of Utah, Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, and the Brecht Forum in New York City.

Michael Hudson

is president of the Institute for the Study of Long-Term Economic Trends (ISLET), a former Wall Street financial analyst, and a distinguished research professor of economics at the University of Missouri–Kansas City. He is the author of numerous books, including Super Imperialism, …And Forgive Them Their Debts, and Killing the Host. More about his work can be found at Michael-Hudson.com.